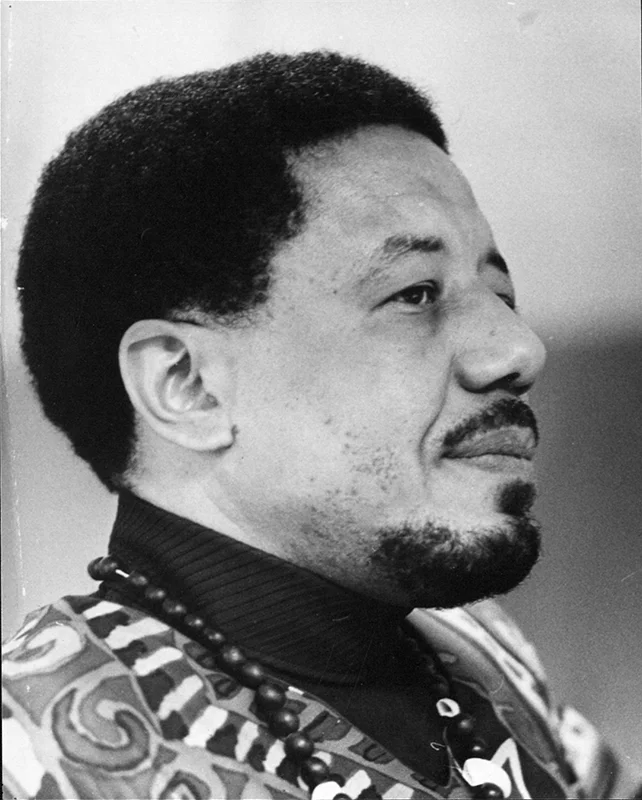

Chester I. Lewis, Jr. Photo courtesy City of Wichita.

Chester I. Lewis, Jr. Photo courtesy City of Wichita.

"We are all born equal, and when we die everyone gets dirt thrown in their face. The only thing that is important is what you do for people. Don't let the wind catch you, or material things cloud your identity and your vision. Just go out and help others." - Chester I. Lewis, Sr., as quoted by his daughter and Chester I. Lewis, Jr.'s sister, Dr. Mary Ellen Lewis London

Chester I. Lewis, Jr. (1929-1990)†, was a Wichita-based attorney and leader in the modern civil rights movement. His contributions to the movement included desegregation in swimming pools and schools, support for restaurant sit-ins, fighting against unfair housing practices, and fighting for economic justice.

Early Life and Family

Born August 8, 1929, Chester I. Lewis, Jr. grew up in Hutchinson, KS with his parents, two brothers, and sister. Hutchinson was the only one of the 12 largest cities in the state that did not segregate school children. Chester Lewis, Sr. delivered the mail and published a newspaper, The Hutchinson Blade, on which the whole family worked.

Both parents were college graduates, his father from Langston University in Oklahoma and his mother with two B.A.s (the University of Kansas and Colorado State Teachers College). Hutchinson schools would not hire her, despite her five years teaching experience. Chester's parents challenged their children to excel. Meal times included spelling bees, quizzes, and discussions.

Chester I. Lewis, Jr. served with the U.S. Army of Occupation in Japan after high school and was one of 40 Black students out of 10,000 at the University of Kansas, graduating in 1951. He entered K.U. Law School, graduating third in his class in 1953.

He moved to Wichita to set up his law practice at 23 with his wife Jackie Rickman (Lewis/Gilbert), who also attended K.U. Later that year, Jackie gave birth to their first child at Wesley Hospital. Baby Michelle was placed in the old bassinets at the back of the nursery, standard practice with Black babies, the nurse told Chester. He immediately demanded to speak to the hospital administrator, threatened to sue Wesley for $250,000, and got the policy changed.

Career

Chester and Jackie volunteered with the local NAACP. Daughter, Brenda Kay Lewis (Davis), was born September 2, 1955. Chester worked as Assistant Sedgwick County Attorney 1954-56 and from 1957-1968 was president of the Wichita branch of the NAACP.

He and Jackie divorced in 1961. Chester married Vashti Crutcher, adding her son Steven Hurley to their family.

He became a national vice president of the NAACP.

After investigating the disappearance of three civil rights workers in impoverished Mississippi in 1964, Lewis changed. He led a five-year national campaign to get the NAACP to address the economic issues that oppressed Black people.

He represented Wichitans who lost family and homes in the 1965 Piatt Street plane crash.

He also organized Black professionals to finance two supermarkets called Brothers in Northeast Wichita to give people access to grocery stores.

In his final court case, he won $16.5 million from the Santa Fe Railroad for Black porters.

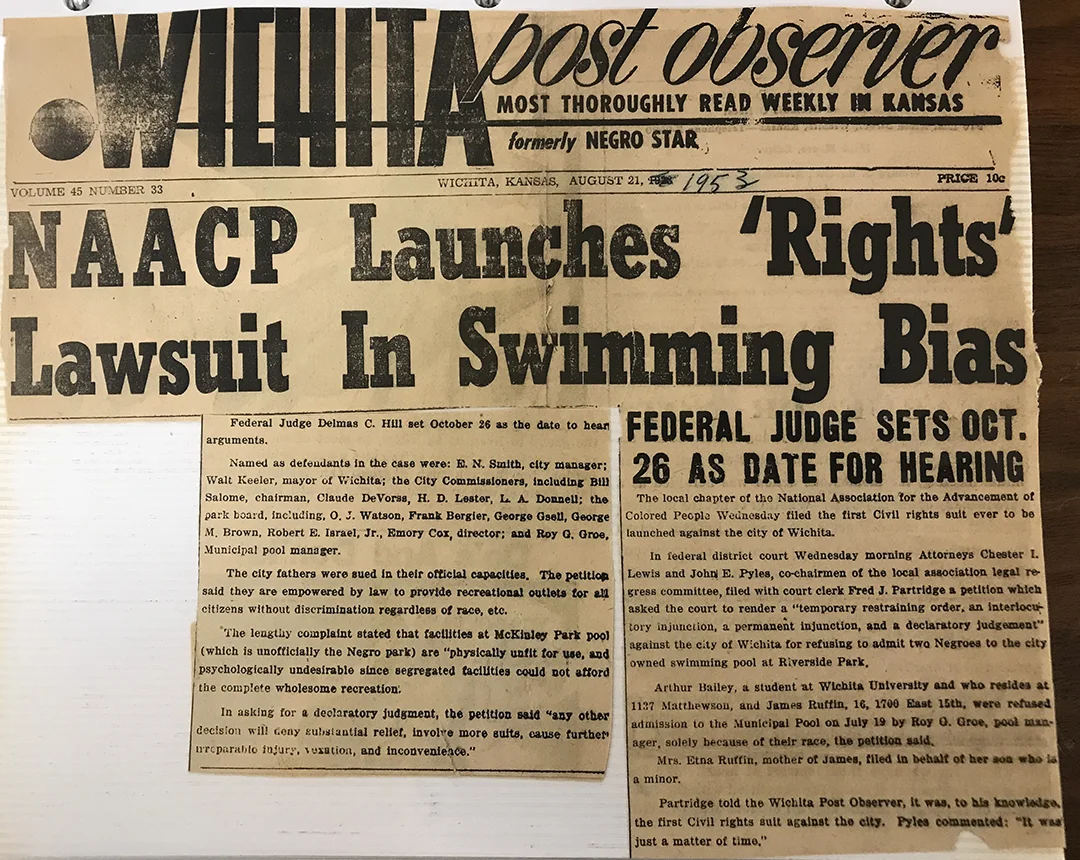

The front page of the August 21, 1953 Wichita Post Observer. The headline reads, "NAACP Launches 'Rights' Lawsuit in Swimming Bias." According to the article, "Arthur Bailey, a student at Wichita University . . . and James Ruffin, 16 . . . were refused admission to the Municipal Pool on July 19 by Roy G. Groe, pool manager, solely because of their race, the petition said."

The front page of the August 21, 1953 Wichita Post Observer. The headline reads, "NAACP Launches 'Rights' Lawsuit in Swimming Bias." According to the article, "Arthur Bailey, a student at Wichita University . . . and James Ruffin, 16 . . . were refused admission to the Municipal Pool on July 19 by Roy G. Groe, pool manager, solely because of their race, the petition said."

Desegregation in Swimming Pools

"The Black Man in America must be accepted fully by the society; he must be granted his full constitutional rights and his just share of power and wealth in America." - Chester I. Lewis, Jr.

Between July 1935 and June 1939, the U.S. government's Works Progress Administration improved or constructed 40 pools in towns across Kansas, but Black people were denied access to them. Black children had to learn to swim in rivers, and drownings were common. Langston Hughes, a famous Black writer who as a child lived in Lawrence, Topeka, and Kansas City, wrote, "Misery is when you find out your bosom buddy can go in the swimming pool but you can't."

In Hutchinson, KS, Chester I. Lewis, Sr., ran a photograph in The Hutchinson Blade of the only pool in Hutchinson available to Black people, a pool filled with algae and lily pads with no room for swimmers.

Chester I. Lewis, Jr., a 23-year-old lawyer new to Wichita, brought the first civil rights suit against the City of Wichita, joined by John E. Pyles. They sued over the denial of access to Wichita's pools in 1953 and won.

Chester I. Lewis, Jr. obtained injunctions against the cities of Parsons and Herrington for preventing Black families from using city pools. As a result, in 1955, The Hutchinson News-Herald reported that "The Kansas Supreme Court ruled . . . [that] the city of Parsons has no right to refuse the privileges of its municipal swimming pool to a . . . Negro."

The state court ruling set the precedent that municipal swimming pools across Kansas must admit Black people. Lewis's action is why the court ruled that people could not be prevented from swimming in city pools across Kansas because of the color of their skin.

Despite this Kansas Supreme Court ruling, hostile whites found ways around the ruling. Pools in Lawrence remained closed to Black people until 1969. After Jackson, MS closed its public pools rather than integrate them, the case Palmer v. Thompson went to the Supreme Court in 1970-71. In a split decision, the Court held, "The closing of the pools to all persons did not constitute a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Fourteenth Amendment to the Negroes."

Banning Black people from public pools may explain why a high proportion of African Americans did not learn to swim and why hurricanes and floods caused so many to drown.

In 1969, Black architect Charles McAfee, a close friend of Chester Lewis, designed the first Kansas pool accessible to African Americans that was properly sized for competitive swimming. In 2021, the award-winning pool was renamed for McAfee.

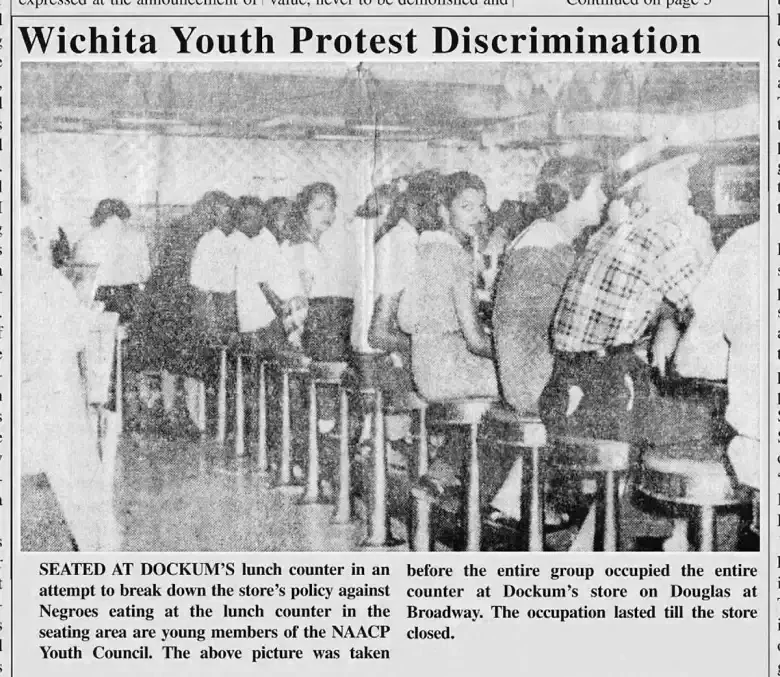

A scene from the Dockum sit-in in the August 7, 1958 issue of The Enlightener. The caption reads: "Seated at Dockum's lunch counter in an attempt to break down the store's policy against Negroes eating at the lunch counter in the seating area are young members of the NAACP Youth Council. The above picture was taken before the entire group occupied the entire counter at Dockum's store on Douglas at Broadway. The occupation lasted till the store closed."

A scene from the Dockum sit-in in the August 7, 1958 issue of The Enlightener. The caption reads: "Seated at Dockum's lunch counter in an attempt to break down the store's policy against Negroes eating at the lunch counter in the seating area are young members of the NAACP Youth Council. The above picture was taken before the entire group occupied the entire counter at Dockum's store on Douglas at Broadway. The occupation lasted till the store closed."

The Dockum Sit-in

"It takes two to oppress: someone to oppress and someone to accept oppression." Chester I. Lewis, Jr.

If you wanted to get a Coke or eat out in Wichita and you were a Black person, you could not sit at the lunch counters but had to take your food and drink outside and eat it on the street. All stores with lunch counters like Woolworths, Kress, Grants, and Rexall (called Dockum in Wichita) followed this policy. But in the summer of 1958, 30-40 Black youth challenged the unfairness of excluding Black people by sitting at the counter for hours waiting to be served. This was called a sit-in.

They were high school and college students, and they sustained their sit-in for three weeks at the Dockum Drug Store at Broadway and Douglas.

Dockum had 9 stores in Wichita and belonged to the largest drug store chain in the U.S. and Kansas.

The students practiced for their sit-in at St. Peter Claver Catholic Church. Their advisor was Mrs. Rosie Hughes. The students would remain nonviolent, even when people threatened them. They went in teams for two-hour assignments led by Carol Parks (Hahn) and Ron Walters. Chester Lewis was their lawyer and inspiration.

When the national NAACP told Wichita's chapter not to allow the sit-ins, Lewis encouraged the local branch to support the students. It did.

After 3 weeks, when they decided to expand the sit-in to every day of the week, the owner told the manager to go ahead and serve them; he was losing too much money.

Chester Lewis phoned the owner:

Are you desegregating all 9 stores in Wichita?

Yes.

All Rexall stores in Kansas?

Uhhhh . . . Yes.

It was the first successful sustained student-led sit-in. Lewis flew participants Ron Walters and Robert Newby in his plane to Oklahoma City, Topeka, and Kansas City to meet with NAACP youth and share what they had accomplished. Sit-ins spread. The national NAACP's Director of Branches, Glouster Current, said in 1960, "[t]he NAACP Youth Council in Wichita, Kansas, in the summer of 1958 sat down in the Dockum Drug Store . . . and desegregated the lunch counter. As a result, integration of lunch counters took place elsewhere throughout the state of Kansas. Of course, there are still some places in this state and city which refuse to accommodate Negroes. The sit-ins spread to Oklahoma City . . . and St. Louis, Missouri in February 1959." The more well-known Greensboro, NC sit-ins took place beginning February 1, 1960, one and a half years after Wichita's Dockum sit-in.

The Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture honors Wichita's Dockum sit-in with a photo of Ron Walters and Carol Parks (Hahn) in its 1950s section.

Under Chester Lewis's leadership, the NAACP continued protests and sit-ins at the other stores that did not desegregate. Some white students and members of the Wichita branch of the NAACP joined the protests. It took 5 years for the other chain stores to change their policy.

Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the national NAACP commended the students for their sit-in.

In Dissent in Wichita: the Civil Rights Movement in the Midwest, 1954-72, Gretchen Cassel Eick describes what happened to the students from the Dockum sit-in:

The students who organized the Dockums sit-in had behind them strong families and a vigilant, encouraging community. One byproduct of segregated housing was a community of Black people of all socioeconomic backgrounds, providing ready access to adult role models with middle-class values. Middle-class mothers by and large did not hold jobs outside their homes while raising children. They monitored the activities of children on their block and volunteered their time through Black sororities; . . . through the women's club movement and the Eastern Star; and through their churches, organizing enrichment activities, competitions, and opportunities to perform that boosted their children's self-esteem . . . . The Black community had to provide activities and opportunities for its children. Segregation prevented them from participating in most of what the majority community offered its children.

The experience strengthened students' aspirations. Most earned advanced degrees including at least three who earned Ph.D.s (Ronald Walters, Galyn Vesey, and Robert Newby).

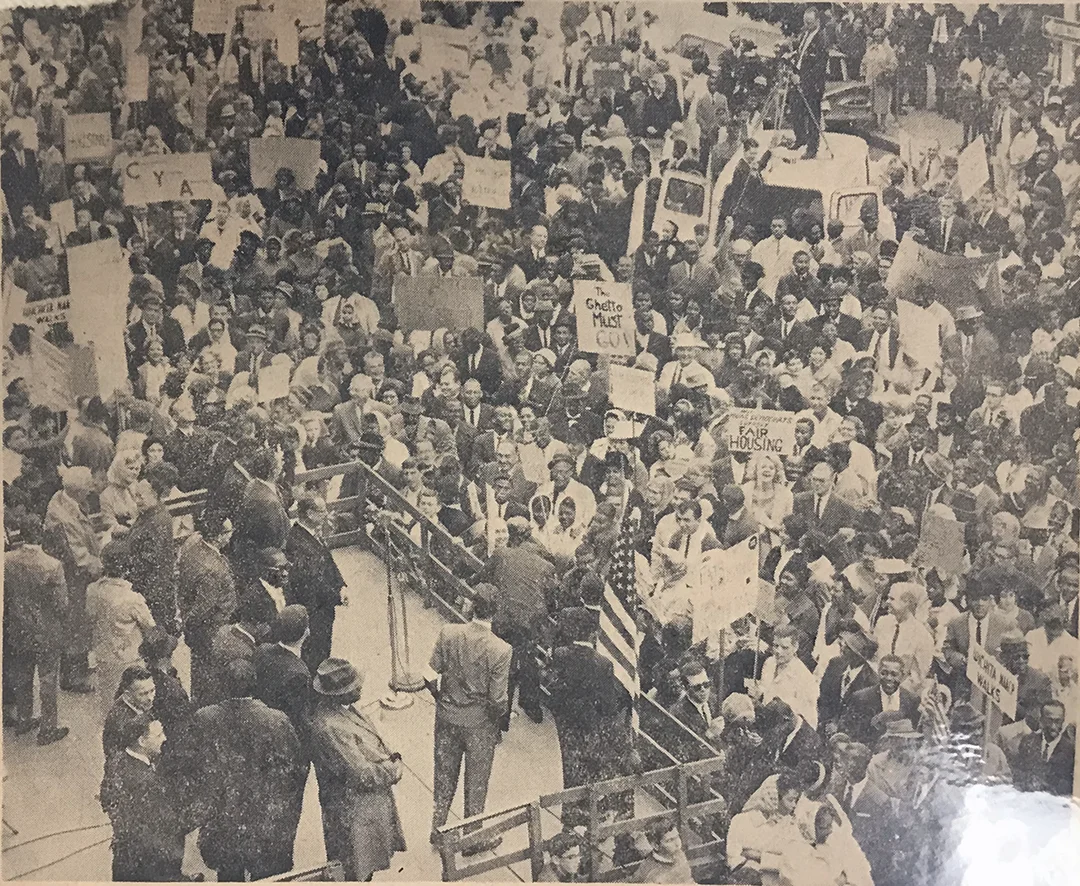

A crowd demonstrates outside of Wichita's city hall, October 27, 1963. Chester Lewis is speaking at a podium while pastors stand behind him. From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Archival Collections at the University of Kansas.

A crowd demonstrates outside of Wichita's city hall, October 27, 1963. Chester Lewis is speaking at a podium while pastors stand behind him. From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Archival Collections at the University of Kansas.

Redlining

"We must set forth a new declaration of independence . . . young and old, black and white, poor and not so poor, are possessed of marvelous energies and constructive ideas, that we all have morale and a character we have not dared to ponder – [so] that America can once more make ourselves, and much of the world, shiver with delight." - Chester I. Lewis, Jr.

Redlining is the practice of discriminating against certain neighborhoods and the people who live there. Banks, real estate agents, and federal agencies worked together to rate neighborhoods using color-coded maps. They refused loans and insurance to people living in neighborhoods marked in red without regard to an individual's qualifications and creditworthiness. In 1937, Wichita was the third most redlined city in the U.S. at 64 percent.

Redlining began during the Great Depression, when two U.S. government agencies – the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) – began offering housing loans to buy homes. FHA offered loans for new housing in the suburbs, which were for whites only. HOLC also offered loans for buying older homes, but denied these loans to people in immigrant or predominantly African American neighborhoods. People were forced to rent housing in racially segregated neighborhoods where landlords could charge them higher rates because they had so few choices of where to live.

Even after the Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that racially restrictive housing practices violated the 14th Amendment, these practices continued. In 1950, Wichita was the 8th most segregated city in the United States. In 1963, Chester and his wife Vashti sought to buy a home, wanting their children to attend Brooks Junior High School. Vashti and her son Steven went on a house tour, accompanied by a white couple who were their friends. They found a house for sale just north of Wichita State University on Roosevelt Street. The neighborhood was all white. Racially restrictive covenants denied any Black person the right to buy property there, despite the 1948 U.S. Supreme Court ruling. The realtor assumed Vashti was the maid of the white couple who bought the house and deeded it to the Lewises.

A portrait of H. Paul Osborn, pastor of the Unitarian Church in Wichita (1962-1967) and co-chair of the Fair Housing Campaign with Vashti Lewis.

A portrait of H. Paul Osborn, pastor of the Unitarian Church in Wichita (1962-1967) and co-chair of the Fair Housing Campaign with Vashti Lewis.

The Fair Housing March

The head of the 60+ member neighborhood association told the Wichita Eagle they were prepared to take legal action to force the Lewis family to leave. Explosives were set off in their mailbox. A rock was thrown through a window. Their cat was poisoned. A cross was burned on their front lawn. Volunteers from Temple Emanu-El and the Unitarian Church formed teams to protect the Lewises.

Many congregations called for a fair housing ordinance that would guarantee that anyone could buy or rent housing regardless of their race, color, national origin, or religion. A coalition led by Vashti Lewis and Unitarian Church pastor H. Paul Osborn presented a petition to the city signed by 1,600 people, including Roman Catholic Bishop Mark Carroll, leading Jewish businessmen, and the school superintendent. They organized the largest demonstration in Wichita's history up to that time on October 27, 1963.

In Kansas, housing discrimination aggressively restricted Black people's access to housing. "The Negroes of Atchison are confined to fairly definite neighborhoods," observed the local NAACP in 1961. Black people were forced into segregated neighborhoods in Newton, Dodge City, Salina, Emporia, Chanute, Wellington, and Great Bend, where they lived "in ghettos near the railroad tracks or in other undesirable areas." Some whites – usually working-class ones – dwelled in more integrated neighborhoods in towns like Hutchinson where "white and Negro do live side by side. Negro settlement is not specific." However, a Hutchinson real estate man confided that, "'if you want to be thrown out of town just go crack a good block with a Negro.' No real-estate man would dare 'crack' a really good block with a Negro." According to the Salina Journal in 1965, "[s]ince there is no fair housing law in Kansas, owners can’t be forced to sell their homes to Negroes."

In 1964, Reflector, a publication of the Kansas Commission on Civil Rights, related a story from Olathe, KS. Air Force Lieutenant Thomas Wilson and his wife Shirley tried to move into the Lakeside Acres subdivision. Before they could move in, "neighbor protest rose to a fever pitch" and residents held a meeting to demand the Wilsons move out. Following the meeting, whites harassed the couple with around-the-clock phone calls, advising them that "We don't mix with Negroes." Before they could move in more than a few of their belongings, the Wilsons moved out again. "We weren't trying to spear-head an invasion of Negroes," Thomas Wilson said.

Neither the city nor the state passed effective fair housing legislation, although the federal government did enact the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

Home ownership is the major way Americans build wealth, but the impact of this discriminatory practice preventing home ownership for Black and low-income people is still being felt today. Redlining and restrictive covenants still exist.

School Segregation and Busing

"The motivation of Black parents to have their children attend 'integrated' schools lies in the proven fact that, if a black child is attending school with white children, the black child can be assured to receiving maximum educational benefits, because the School Board isn't going to stunt or short-change white children." - Chester I Lewis, Jr.

Kansas law allowed cities in the state to require Black children, ages kindergarten through 8th grade, to attend separate schools based on the color of their skin. Most cities in Kansas, including Wichita, did this. The practice was called segregation.

Over the years, a number of legal cases attempted to fight segregation in Kansas schools:

- Elijah Tinnon v. The Board of Education of Ottawa (1881)

- Knox v. The Board of Education of Independence (1891)

- Reynolds v. The Board of Education of Topeka (1903)

- Cartwright v. The Board of Education of Coffeyville (1906)

- Rowles v. The Board of Education of Wichita (1907)

- Williams v. The Board of Education of Parsons (1908)

- Woolridge v. The Board of Education of Galena (1916)

- Thurman-Watts v. The Board of Education of Coffeyville (1924)

- Wright v. The Board of Education of Topeka (1929)

- Graham v. The Board of Education of Topeka (1941)

- Webb v. School District No. 90, South Park, Johnson County (1949)

Then in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education that segregation in public schools was against the law. However, it took nearly twenty years for the Wichita school board to integrate its schools. More than 90 percent of Black families lived in one area, northeast Wichita, and the school board kept redrawing school attendance boundaries to prevent children from that area attending schools in other neighborhoods. Chester Lewis, the NAACP, Black organizations, and Black parents often petitioned the school board to end separate schools. In response to a letter from Lewis, USD 259 reassigned a small number of Wichita's Black teachers to predominantly white schools, but that was all.

In January 1966, Lewis flew to Washington, D.C. and filed a complaint with the federal government. He included 300 pages of documentation showing that Wichita still maintained a school system that assigned children to schools according to their race.

The U.S. government investigated Wichita Public Schools from 1967-71. It was the first investigation of school segregation in the Midwest. When the U.S. government said it would withhold $5 million of federal aid to Wichita, the school board agreed to bus Black children to white schools and a small proportion of white children into schools in the northeast area. Chester Lewis opposed this decision, saying it was unfair to Black families.

The busing plan was accepted by the school board for the 1971-72 school year and remained in place until 2008.

The front page of the October 22, 1960 Kansas Sentinel. The headline reads: "Suit Filed Against Kansas For Unfair Employment Practices Toward Negroes." According to the story, "Donald L. Pryor of Wichita, Kansas through his attorney, Mr. Chester I. Lewis, filed a suit in the District Court of the United States, against State Employment officials charging wholesale race discrimination by the officials in placing Negroes on jobs in Kansas."

The front page of the October 22, 1960 Kansas Sentinel. The headline reads: "Suit Filed Against Kansas For Unfair Employment Practices Toward Negroes." According to the story, "Donald L. Pryor of Wichita, Kansas through his attorney, Mr. Chester I. Lewis, filed a suit in the District Court of the United States, against State Employment officials charging wholesale race discrimination by the officials in placing Negroes on jobs in Kansas."

Economic Justice for African Americans

"It must be realized that despite arguments that Rome wasn't built in a day or that racial problems can't be cured overnight, 100 years is an awful lot of darkness, and Negroes are sick of evasions, weary of excuses, tired of technicalities, fed up with promises, and want action, freedom, and equality now." - Chester I. Lewis, Jr.

Chester Lewis challenged employment discrimination of Wichita's largest employers in aircraft, the railroad, telecommunications, and the State and City governments, citing violations of Kansas and Federal law. And he won. Consistently.

In Dissent in Wichita, Gretchen Cassel Eick notes:

In May 1961 the state legislature passed the Kansas Act against Discrimination, a triumph for the NAACP. The law created a Kansas Commission on Civil Rights (KCCR) that had enforcement power. The act prohibited discriminatory employment practices based on race, color, religion, or country of origin and empowered the KCCR to investigate complaints, hold hearings, mediate redress, and, if conciliation failed, issue cease and desist orders. Complainants were protected from reprisals. Violation of the law was a misdemeanor and would bring a fine of up to $500 and/or imprisonment for up to one year. The majority of cases that would come to KCCR in the following year would come from Wichita, and often Chester Lewis would be involved . . . ."

That same year, Lewis filed a federal complaint that ended the practice of the Kansas State Employment Service accepting racial designations like "whites only need apply."

In 1966, Chester Lewis sent a formal complaint to the U.S Equal Opportunity Commission on behalf of Margaret Daniels, one of only three Black women employed by Cessna. Ms. Daniels had requested transfer from being a maid to the sheet metal training class. Her request was denied. Her supervisor told her if she didn't drop her grievance, she'd remain a maid all of her life. Daniels asked her union to investigate, but they refused.

This photograph appeared in the January 6, 1983 Kansas Black Journal under the headline "71 porters awarded $6 million." Chester I. Lewis, Jr. is in the front row, third from the right. From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Archival Collections at the University of Kansas.

This photograph appeared in the January 6, 1983 Kansas Black Journal under the headline "71 porters awarded $6 million." Chester I. Lewis, Jr. is in the front row, third from the right. From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Archival Collections at the University of Kansas.

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad employed Pullman Porters, who were part of the first all-Black union, The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, founded in 1925. They expanded the Black middle class. They were on call 24/7 with no overtime pay, yet delivered their service with excellence. They had a pivotal role in launching the largest migration in U.S. history, also known as the Great Migration. Black people left the Jim Crow South, motivated by stories in Black newspapers that porters distributed that told of opportunities for a better life in northern and western cities. In 1984, Chester Lewis sued the Santa Fe Railroad and won $8.5 million for Black porters, who had been underpaid from the 1920s-1970s. An additional $16.5 million was awarded from a second lawsuit.

Lewis flew people to Washington, D.C. in his private plane to lobby for passage of a national law that became the 1964 Civil Rights Act. That law made discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, or gender in employment, education, and public accommodations a federal crime.

A portrait of Chester I. Lewis, Jr., circa 1964. From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Archival Collections at the University of Kansas.

A portrait of Chester I. Lewis, Jr., circa 1964. From the Kenneth Spencer Research Library Archival Collections at the University of Kansas.

The Legacy of Chester Lewis

In a letter to the editor of The Wichita Beacon on February 22, 1957, Chester I. Lewis, Jr. wrote:

"Here in Wichita Negroes are denied the right to find employment suitable for their abilities, to own homes in desired locations, and to enter many places of amusement and public accommodation. This is our land . . . . We helped to build it. We have defended it from Boston Common to Iwo Jima. We have made it a better land through our songs, our laughter, our expansion and clarification of its Constitution and its Bill of Rights, through our talents and skills, all the way from Benjamin Banneker, who helped lay out the city of Washington, D.C., to Ralph Bunche, who made the work of peace a reality in 1949. We are Americans and in the American way, with American weapons and with American determination to be free, we intend to slug it out, to fight right here on this home front if it takes forty or more years until victory is ours."

Mr. Lewis filed 68 civil rights lawsuits and obtained numerous injunctions that provided opportunities for African Americans to gain more access to housing, jobs, swimming pools, restaurants, and schools in Wichita.

Chester I. Lewis, Jr. died on June 15, 1990, age 60.

Chester I. Lewis Reflection Park

On January 9, 2007, the Wichita City Council voted unanimously to rename Reflection Square Park at 205 E. Douglas to Chester I. Lewis Reflection Park. Since the year 2000, the park, which was at the site of the former Woolworth's building, had included a bronze sculpture depicting a lunch counter scene. The sculpture was one of eleven by Washington artist Georgia Gerber along Douglas in downtown Wichita, paid for with $500,000 from the DeVore Foundation.

Park Remodel

Construction began in 2020 to remodel the park and surrounding area. The bronze lunch counter sculpture was placed into temporary storage with the intent of relocating it to Finlay Ross Park, 123 W. Douglas. The remodeled Chester I. Lewis Reflection Square Park is the first publicly funded art project in downtown Wichita depicting an African American. A ribbon cutting was held on September 16, 2023. Artists Ellamonique Baccus and Matthew Mazzotta and members of the Lewis family spoke at the event.

The new artwork has two distinct approaches that co-exist in the same space, BEYOND by Matthew Mazzotta and WINDOWS, WALLS, AND WINGS by Ellamonique Baccus.

Matthew Mazzotta

American, born 1977

BEYOND, 2022

Galvanized steel, paint

City of Wichita Public Art Collection

BEYOND is a site-specific artwork for Chester I. Lewis Reflection Square Park. It is composed of a series of vertical structures called Echos that are distributed across the park and progressively shift from the shape of a house into a park open for all. The concept of a house opening its roof and walls as it expands across the park symbolizes inclusion. It references the housing policy that Mr. Lewis redefined in his lifetime and the continued impact of his work in breaking the barriers of segregation and oppression in all areas of daily life.

The Echos sequentially opening to the sky signals another concept: amplification. Mr. Lewis was a prominent orator on both the local and national levels, and he fought to overcome many injustices. The design of the Echos radiating outward from the central house and stage area—makes his words visible as they are continually broadcast to the larger world.

Ellamonique Baccus

African American, born 1979

WINDOWS, WALLS, AND WINGS, 2023

Glass, aluminum, steel, ceramic tile

City of Wichita Public Art Collection

WINDOWS AND WALLS is composed of oil paintings by Ellamonique translated to monolithic glass. The work is meant to be an opportunity to understand and connect on a human level to the tests and triumphs of Chester I. Lewis as his life and work transformed the African American experience in Wichita. WALLS references the barriers yet to be overcome.

The WINGS atop Mazzotta's house structure and the benches represent the Principles of Ma'at, which are truth, justice and harmony. This is the foundation upon which the legal system is built and the values upheld by attorney Chester I. Lewis.

The mosaic beneath the house structure depicts the REDLINING MAP of WICHITA, a color-coded map that was used to restrict homeownership in 63 percent of Wichita.

The works are accompanied with poetry by Ellamonique Baccus and a virtual audio tour written by Dr. Gretchen Cassel Eick and narrated by Carla Eckels.

Artist's Response

Local artist Robert Bubp was inspired by the remodeled park and the story of Chester I. Lewis to create Geo Logic: Will Not Be Unseen/Find the Holes in the System, Wichita, Ks. This artwork is on display at the Advanced Learning Library. Bubp describes his work:

This artwork refers to a 1937 map showing the extent of Wichita's "redlined" areas, encompassing about 50% of the city; redlining was a discriminatory housing practice that often limited people of color to live in specific areas of a city that had been termed high-risk by the FHA for housing loans. Overlapping most of the historic redlined area is a bright pink 2024 U.S. Housing and Urban Development map identifying areas of Wichita classified as "difficult to develop," a signifier of economic disadvantage. (https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sadda/sadda_qct.html)

Circled and numbered "hot spots" identify historic sites where civil rights lawyer Chester I. Lewis' actions impacted laws, policies, and public life in Wichita to end discrimination and segregation.

1. Wesley Hospital, 1953: Chester I. Lewis and his wife, shortly after moving to Wichita, had a baby at Wesley Hospital, 550 N. Hillside; upon seeing babies of minorities segregated from white ones, Lewis threatened a lawsuit based on an 1874 Kansas law prohibiting segregation in public accommodations. The hospital changed its policy. (Eick, 39.)

2. Riverside Pool, 1953: Lewis and John E. Pyles sued the City of Wichita for denying entry to Riverside Pool to two Black college students, resulting in desegregation of all municipal pools. Believed to be the first civil rights lawsuit filed against the City of Wichita. (Eick, 39.)

3-6. Additional public pools, 1953-54: The effective legacy of Lewis's actions regarding desegregation of municipal pools, resulting in open-access to additional municipal pools built during Lewis' civil rights era:

3. Aley Park Pool, 1803 S. Seneca St., believed 1950s;

4. Edgemoor Park Pool, 5815 E. 9th St., 1966;

5. McAdams (now McAfee) Pool at McAdams Park, 1329 E. 16th St., 1969;

6. Linwood Park Pool, 1901 S. Kansas St., 1971.

7. Lewis residence, 1957: Lewis and family built a residence on N. Madison Ave. in 1957, but were unable to secure bank or FHA financing because of redlining practices; the home was outside the Black section of the city at the time (Eick, 40), though it was within the areas of the 1937 redlining and 2022 "difficult to develop" maps.

8. Dockum Drugstore Sit-In, 1958: Douglas & Broadway-"Along with the other variety stores clustered downtown on or near the corner of Douglas and Broadway... Dockum's was one of the places to stop for a Coke and rest your feet while shopping. But if you were black, there was no resting allowed inside the stores; a Coke, once purchased, had to be consumer outside." (Eick, 1). African-American high school and college students were organized by Chester Lewis and the local chapter of the NAACP--whose national organization at the time did not endorse sit-ins. The locals did it anyway, occupying seats at the Dockum lunch counter Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays from July 9 well into August. They sat face-forward as if expecting to be served, with no other distractions or activities, for all the hours the counter was open those three days of each week. They were cursed and defamed on a regular basis, and on a few occasions left when threatened by police; on August 7, they fended off the threat of a brawl with a white student gang by calling in supporters from other community centers to outnumber the potential aggressors, then left the drugstore. The following Monday, August 11, Dockum's agreed to serve Black customers at the lunch counter because of its extreme revenue loss during the sit-in period. The policy across the state was changed immediately. The success of the Dockum sit-in led to subsequent sit-ins in Winfield, Ks., and Oklahoma City, with the NAACP eventually changing its policy toward sit-ins and encouraging them, creating significant momentum for the burgeoning civil rights movement. (Eick, pp. 1-11.)

9. Lewis house, 1963: N. Roosevelt, north of WSU - this newly-constructed neighborhood had a whites-only compact, the sort of which had been ruled by the Supreme Court in 1948 to be legally unenforceable; Lewis' wife Vashti Crutcher Lewis and white friends duped the seller into believing the Lewises were white by Vashti touring the house as the "live-in maid" and then having the white couple deed the house to the Lewises after the sale (Eick, 77).

10-12. Plans for a new school on the northeast side, 1965: Plans for W. C. Coleman Middle School led to a crisis regarding boundary lines and their effect on the racial balance of nearby Wichita schools Brooks Intermediate and Mathewson Intermediate. The new school was proposed by the school board to be white only, and Mathewson was already mostly Black-which would have perpetuated the (now illegal, per Brown v. Board of Education) "separate but equal" approach to school population. Additionally, the Black parents at Mathewson did not want their children to attend a Black-only school. Lewis filed a federal lawsuit against USD 259 as a response to the proposal, resulting in Wichita being the first midwestern school district investigated by the new Office of Civil Rights. The OCR did not change the USD proposal, but did require new construction at Isley Elementary on N. 18th St. as a result. (Eick, pp. 109-113).

10. Brooks Intermediate, 3802 E. 27th N.;

11. Mathewson Intermediate, 1847 N. Chautauqua, & Isley Elementary next door;

12. Coleman School -1544 N. Governeour Rd.

13. Brothers Grocery Stores, 1967-Lewis and others led efforts to fund the opening of two Black-owned Brothers Grocery stores in the northeast area, at 17th & Poplar and at N. 13th St. (Eick, 134).

It must be noted that this list of places in Wichita impacted by Chester I. Lewis' activism is not exhaustive. Research for this project was largely via Gretchen Cassel Eick's Dissent in Wichita: The Civil Rights Movement in the Midwest, 1954-72, Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illinois Press, first paperback edition, 2008. Special thanks to Ellamonique Baccus for recommending it.

Notes

†Some sources cite Chester Lewis's year of birth as 1929, while others cite 1928.

Additional Resources

More about Desegregation in Swimming Pools

More about the Dockum Sit-in

- "'Hope For The Future': The Dockum Sit-In, Sixty Years On" by Carla Eckels, KMUW, August 10, 2018

- The Dockum Sit-in: A Legacy of Courage documentary by KPTS, 2009

- "How the Dockum Drug Store sit-in blazed a trail for civil rights" by Sheinelle Jones, NBC's TODAY Show, February 1, 2021

- "The brave, forgotten Kansas lunch-counter sit-in that helped change America" by Kate Torgovnick May, Washington Post article, February 6, 2021

More about Redlining

- "For people of color, banks are shutting the door to homeownership" by Aaron Glantz and Emmanuel Martinez, Reveal, February 15, 2018

- Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America

- "Racial covenants, a relic of the past, are still on the books across the country" by Cheryl W. Thompson, Cristina Kim, Natalie Moore, Roxana Popescu, Corinne Ruff, NPR's Morning Edition, November 17, 2021

- "Plessy's Legacy: The Government's Role in the Development and Perpetuation of Segregated Neighborhoods" by Leland Ware, RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, February 2021, 7 (1) 92-109

- "Highway to Nowhere" by Pilar Pedraza, KAKE News, February 28, 2023 - Part 1 | Part 2

More about School Segregation and Busing

More about the Legacy of Chester I. Lewis, Jr.

More about the Civil Rights Movement